A collaboration with Nindityo Adipurnomo to participate at ‘Grandeur’ exhibition and procession at Sonsbeek park and the city of Arnhem, The Netherlands.

The procession

The opening of the 2008 edition of Sonsbeek was a procession of art works, carried by citizens of Arnhem from the city to the park, where the art works would be displayed for the three-month summer exhibition. We interpreted the theme ‘Grandeur’ as a series of opposites; the majestic as opposed to the ordinary. The act of lifting and carrying the artworks around implies that there is a value attached to the objects. The objects become symbols or even fetish objects. It raises the questions: What is the significance of this procession? What or whom is it held in honour of? What is important enough to be carried in a procession? And who should have the right to be the objects’ bearers?

The people that lift and carry the objects channel the strength of the objects. Not only do the objects become fetish objects but a certain importance or significance is attached to the carriers, and eventually to the creators of the objects.

Working with the idea that objects carry a certain power, we decided to study Javanese and other Indonesian cultures, as there are around 300 diverse cultures in Indonesia. Very frequently meanings, values and forces are given to objects; this is called ‘animism’, the modality and source of cultural richness in Indonesia. Its origins can be traced back to centuries before the arrival of religion in Indonesia. Animism is a belief system through which reality is perceived. This belief system assumes that the seen world is related to the unseen; an interaction exists between the divine and the human, the sacred and the profane, the holy and the secular. It is related to the worshipping of nature and ancestors; the animist presupposes that spiritual beings and forces, which have power over human affairs, control all forms of life. Through time, these animistic values have been adopted by and have become part of all religions of Indonesia. Although we live in the modernized and globalized society of Yogyakarta, this belief is still very much a part of daily reality.

For ‘The Last Animist’, we invited migrant families from different countries that settled down in Arnhem, to become participants or “carriers” in the procession. There were newcomers as well as families that had lived in the Netherlands or Arnhem for many generations. Starting from the idea that objects carried in a procession are somehow valuable, we asked the families to carry a cherished object related to their land of origin and/or personal history. Each family’s object of choice had its own story to tell.

Through this process, we found that their cultural roots and family histories were often glorified, stuck in a time loop. The emphasis on “authentic” culture is something we see in migrant communities all over the world. We could say it’s sentimental, absurd or over-romanticized and often far removed from the contemporary reality in their country of origin, which has developed over time. Families keep their own (oral) histories alive and keep objects to strengthen their memories, myths and histories.

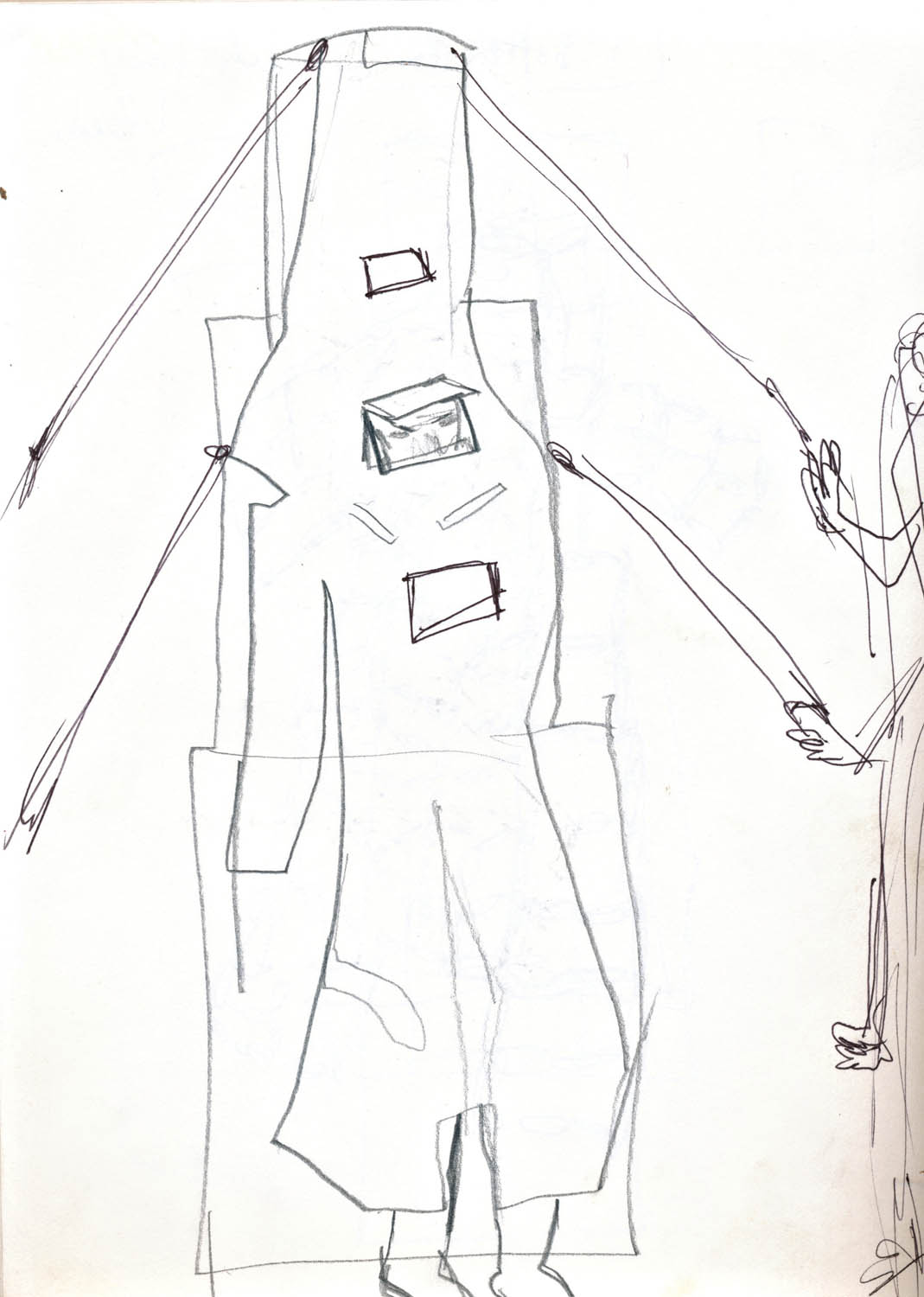

For the Sonsbeek exhibition, we designed nine buildings, starting from the idea of the container (building/construction) and the content (the objects). Some of the “buildings” were carried in the procession. Afterwards, they were installed in the park together with copies of the personal objects. The blueprint of the installation in the park was inspired by the floor pattern of most palaces in Java, which is based on our nine human orifices: the eyes (2), the nose (2) the mouth (1), the ears (2) the genitals (1), the anus (1). We created various open structures, like carcasses or architecture skeletons, inspired by Javanese and Balinese architecture, a roof on pillars acting as the basic structure. The constructions were made of different materials such as wood, aluminium, buffalo horn, bones, wire, electronics, cocoons, etc.