‘I owe you’ is an installation with costumes, video, and sound, related to the research on barkcloth.

Clothing as a state of control

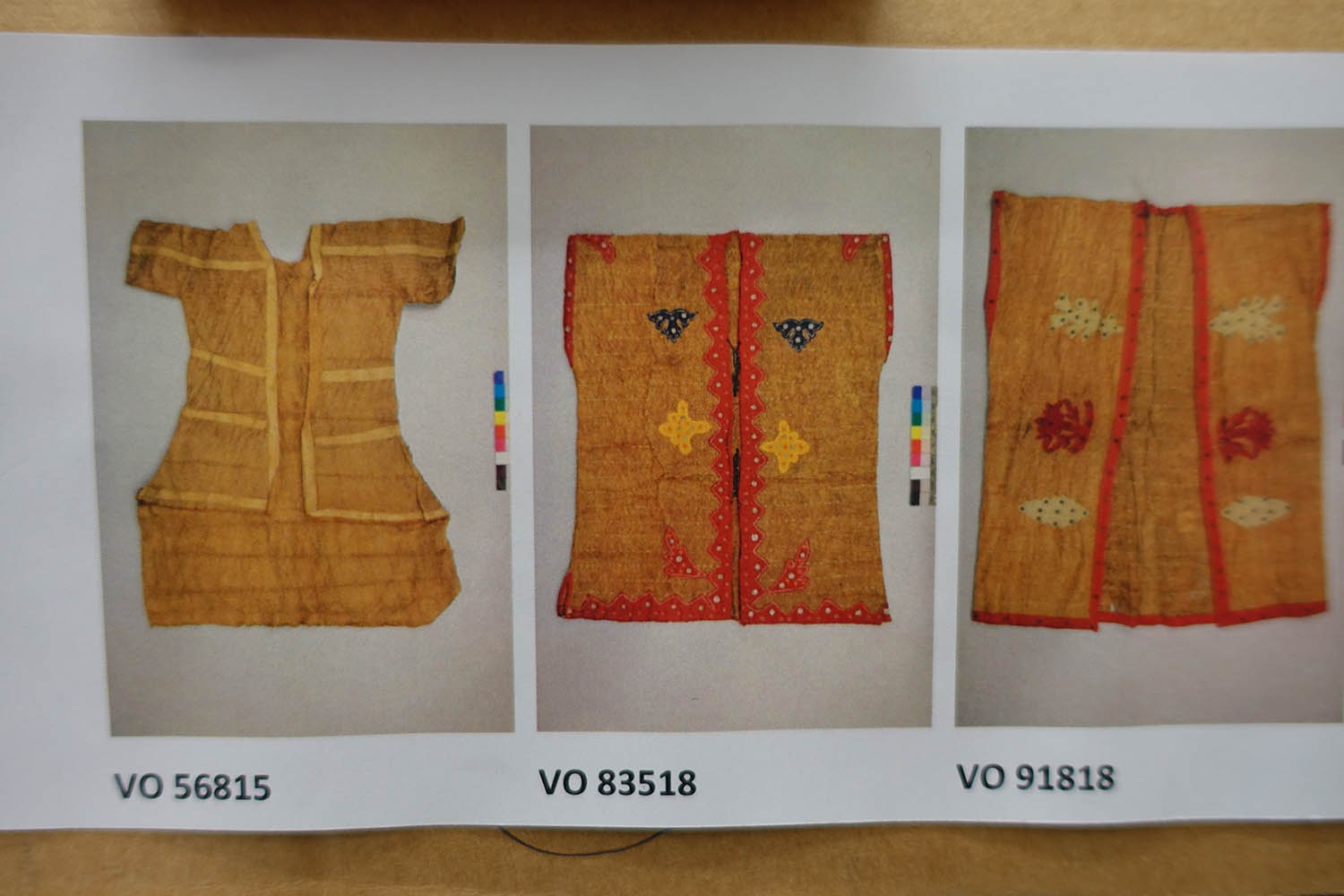

My work for the exhibition at Europalia is based on my experience that I had during the residency at the Weltmuseum in Vienna in May 2017. Doing artistic research in the storages, photo archives, databases and library expanded my interest in the history of clothing. I was introduced to materials other than loomed textiles. At the Weltmuseum I discovered and researched the barkcloth collection. I also found pubic covers made of coconut shells and leather warrior jackets decorated with shells, all from Sulawesi.

First I looked into what kind of people started collections during the colonial time period and how they did this. There are different approaches and interests of collecting objects and knowledge. Collectors included travellers on expeditions, military doctors, colonial administrators, scientists, and missionaries. All of these collectors have different interests and agendas. What they have in common is that during the colonial era, research and writings were focused on the material culture. Collectors described how the objects they found were made and used, but the works present little information about the actual life of the people themselves (Koentjaraningrat, Anthropology in Indonesia, 1975). The world museums in Europe recently underwent a shift from emphasizing “the object” to highlighting “the people,” but their main focus remains “the object,” its preservation, and “the object” as a source of creating knowledge.

During the Dutch colonization, missionaries (Catholic and Protestant) lived closest to the local people in remote areas. It wasn’t until 1900, however, that they started to write more about the Indonesian inhabitants. Historiography and anthropology were recorded under colonial rule by persons in positions of authority. These records contained a strong bias against traditional Indonesian customs which were described and stereotyped as heathenistic, primitive, and superstitious. Methods of compiling data were improved after 1920 through compiling ethnographies that were developed in other parts of the world.

I became interested in fuya, or the so called barkcloth in Sulawesi, because of the way in which the role of this specific fabric reflects the account of history. It documents social patterns and its decline through Christian contacts, Islamic influences, and the unavoidable processes of modernisation.

The first persons who wrote intensively about the barkcloths were two scholarly Dutch protestant missionaries, N. Adriani and Alb. C. Kruyt, in 1905 (Geklopte Boomschors als Kleedingstof op Midden- Celebes). They studied local cultures and languages in Indonesia and they wrote that bark cloth was the original clothing material of the entire Indonesian archipelago before woven textiles were invented or introduced.

I came across an article, however, by the same Alb. C. Kruyt, the protestant missionary and researcher of barkcloth, who wrote in his essay The Influence of Sending on the society of Inlanders;

“The Sending brings Christianity. As something new, which the ancestors were not familiar with, they stand hostile to the practical consequence of the Christian: the abolition of all kinds of pagan customs. The preaching of God leaves them indifferent for the time being: the gods of the Gentiles are the spirits of their ancestors; These only represent an interest in their descendants; They are therefore indifferent to those strangers, the Dutch. But, on the other hand, they cannot think otherwise, whether the God of Christians must be indifferent to them, because God alone has an interest in his descendants.

Slowly, the spoken word speaks to them: the Gentiles become Christians, either because they acknowledge the powerful in the God of Christians, or because of political reasons; Usually one comes with the other, but they repent, they become Christians. What does that mean? This means that the yoke of its own spirits has been thrown away, and that one has stood under the protection of the God of Christians. Certainly there will also be among those who can testify of a religious-moral renewal, but nothing else has happened to them, except that they have come into a different environment. But this new environment is of great significance for their society. With the new religion, they have in principle adopted the society of the representatives of that religion. The Inlander immediately feels connected to the new society after his transition, and one of the first things in which he takes this form is to adopt European dress. Those who feel something for the social benefit of the Mission must be delighted to this phenomenon, because changing the dressing is a very big proof.”

While the early field researchers like Kruyt and Andriani were interested in local meanings of the barkcloth designs and the processes by which they were produced, they were also responsible for forcing the Sulawesi people to abandon the barkcloth-making and ritual painting process and replace the barkcloth clothing with textile clothing and convert to Christianity from Animism. Despite this, the production of finer barkcloth used to make men’s headscarfs, ponchos, and shoulder bags which were painted with meaningful designs were still used in major rituals which took place around puberty, marriage, death, yearly harvests, and for the purpose of healing.

Barkcloths were worn in the 20th century for different social reasons. Depending on the area, these cloths were worn forspecial occasions when rituals took place in relation with pagan traditions. These traditions were assimilated with Christianity as well as produced and worn in opposition to Christian dominance. Barkcloths were also associated with poverty:

“Only during two periods of textile scarcity was indigenous barkcloth production vigorously revived through necessity. During both the Kahar Muzakkar Islamic rebellion (disturbing various regions of Sulawesi between 1950 and 1965) and World War II, Central Sulawesi women returned to their ancestral technology in order to clothe their families. From 1941 to 1945 almost no woven cloth could be obtained due to the Japanese occupation. Many people were reduced to wearing meagre loincloths of bark-cloth or coconut fibre sacking, a situation that elders still recall vividly. (Lorraine V. Aragon, Barkcloth Production in Central Sulawesi – A Vanishing Textile Technology in Outer Island Indonesia, 1990).”

Barkcloths cannot be washed and the sarongs, loincloths, and tunic blouses could be worn on a daily basis for no longer then seven or eight months. Barkcloth’s production is much faster than loomed cloth. It takes around ten days. With the introduction of woven textiles, however, barkcloth is now an almost extinct process of manufacturing clothing. Additionally, during the last decade most barkcloth sacred objects were part of rituals that have been eliminated due to increasing Christianization mostly inland and Islamization of the coastal areas.

Although the Weltmuseum in Vienna and The Tropen Museum in Amsterdam currently have an extensive collection of barkcloths, there is little attention given to this important item of Indonesian material culture. In Indonesia, I just rarely come across barkcloth collections because the usual focus is on batik and ikat and because very few scholars do research on this subject.

Links to Project: